Benefits of retrofit include warmer, more comfortable homes, better health, lower bills and reduced energy use. These benefits can also be achieved through building new homes, so why prioritise retrofit of housing estates over demolition?

The UK’s social

housing crisis

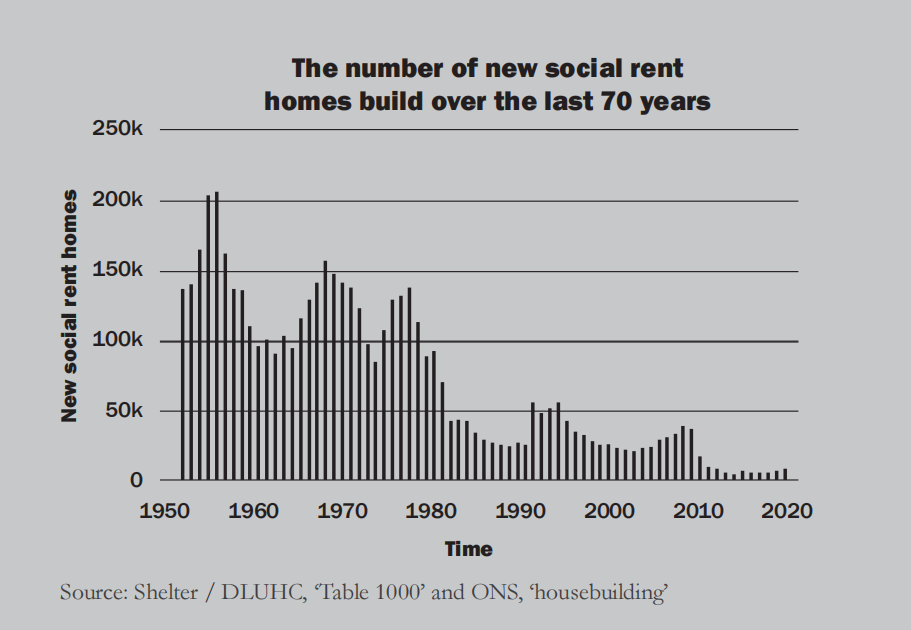

Between 1946 and 1980 the UK’s local authorities and housing associations built 4.4 million homes for social rent, housing over a third of the UK population by the late 1970s. However, because of the Right-to-Buy and the estate regeneration programme, now only 17% of the population live in social or council housing. According to the Office for National Statistics, in the past ten years, there has been a total loss of 177,487 social homes.

While deteriorating social housing conditions and shortages are reasons given for estate demolition and ‘regeneration’, the real target was, and remains, the high- value urban land on which housing estates are built.

The current funding model for estate regeneration is based on demolition of existing social and council homes, and construction of new dwellings for sale to subsidise the replacement of the demolished homes. This relies on significantly increasing the density of development, up to four times the floor area on the same site. However, due to the high cost of demolition and redevelopment the number of additional social homes is often minimal. In the proposed £600m rebuilding of West Kentish Town Estate, for example, only 13 out of a total additional 569 homes are proposed to be for social rent.

Communities are destroyed by such demolition and construction projects which can last for decades. Countless residents have been evicted from their homes, often forced into the unaffordable and poorly regulated private rental market with consequent negative economic effect. Due to poor compensation, leaseholders and freeholders also cannot afford to return to the redeveloped area.

The social and health consequences of the destruction of whole communities are devastating, particularly for poor families, children and the elderly who benefit the most from the informal social infrastructures found on working class housing estates.

The high risks and high costs of such large scale projects no longer guarantee the profits of previous decades. As a result, there are stalled estate regeneration projects across the UK where homes have been demolished and people have moved away but the developer lacks funds to complete the development.

This exhibition demonstrates viable and less risky alternatives to demolition. In these schemes for retrofit, refurbishment and infill, residents can stay in their homes, communities can persist, and additional social homes can be provided.

The housing crisis should be addressed in a way that minimises harm to the environment. By retrofitting existing homes wherever feasible we can minimise resource use and carbon emissions.

The environmental

cost of construction

The built environment and construction sector accounts for 38% of global carbon emissions and it has been estimated that globally we build the equivalent of a city the size of Paris every week. Presently, the way we produce, operate and renew our built environment harms biodiversity, pollutes ecosystems and threatens well- being.

The Intergovernmental Committee on Climate Change states with high confidence that “Human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming.”

Carbon dioxide is an important greenhouse gas. ‘Carbon emissions’ are released by burning fossil fuels – coal, gas and oil – in power stations, vehicles, and boilers. Other contributors include cutting down and burning forests, chemical industrial processes like making cement and heat- related processes such as making bricks and steel. The construction industry involves many stakeholders with long supply chains operating across many countries and carbon emissions are therefore difficult to track.

The carbon emissions resulting from the manufacture and transport of construction materials and construction of a building, is known as ‘embodied carbon’, measured in tonnes of CO2e. ‘Embodied carbon’ is not stored in the building fabric itself, and the

existing embodied carbon is not relevant to the challenge to reduce emissions.

‘Operational carbon’ is the name given to emissions from energy use for heating, cooling, ventilating and powering buildings. Whilst the requirement to reduce operational carbon is legislated for in the UK by the Building Regulations and Climate Change Act of 2008, reducing the embodied carbon of construction is not, partly because a large proportion of the emissions are generated outside the UK so there is no requirement to account for them under the UN Paris Agreement of 2015.

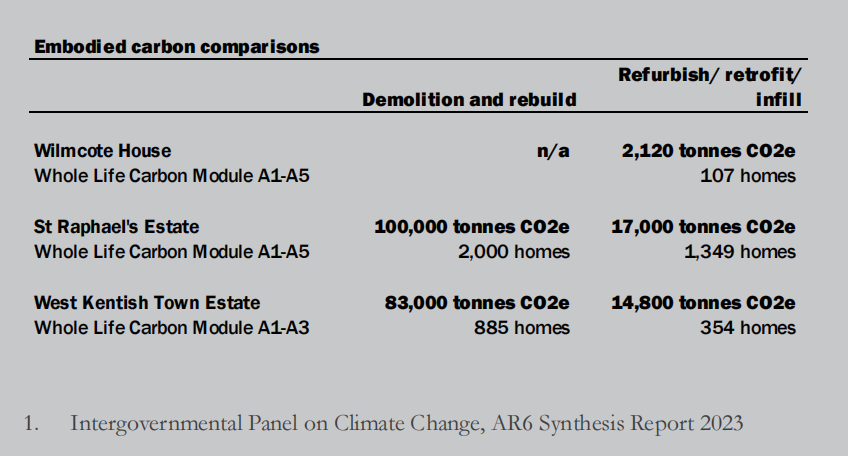

Repairing, refurbishing and retrofitting existing buildings avoids the high environmental cost of constructing new buildings. The construction of retrofit schemes requires less material and processes than demolition and rebuilding and produces significantly less carbon emissions overall.

Industrialised nations should be aiming to address the climate and ecological crisis systemically. To do so means escaping the ‘business-as-usual’, growth-based approach in order to reduce the huge amount of new construction currently occurring.

The case studies in the exhibition have had their embodied carbon calculated and this is compared against a demolition and rebuild scenario here:

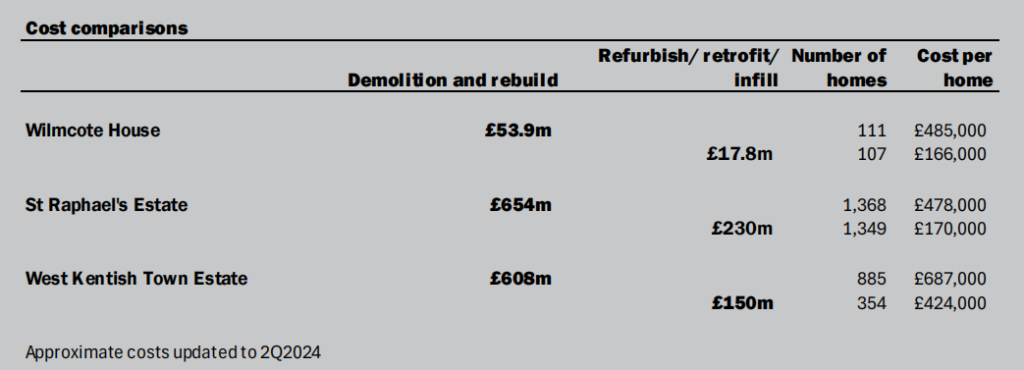

Cost considerations of ‘demolition and rebuild’ versus retrofitting existing homes

Funding and

retrofit strategies

As the exhibition shows, the financial costs of retrofitting are considerably less than for demolition and rebuilding. However, these works still need to be paid for and the ‘lack of adequate funding’ is one of the key arguments cited in arguments against retrofit.

As the exhibition shows, the financial costs of retrofitting are considerably less than for demolition and rebuilding. However, these works still need to be paid for and the ‘lack of adequate funding’ is one of the key arguments cited in arguments against retrofit.

In cases where there is no opportunity for new build cross-subsidisation – such as in the case of Wilmcote House – all of the funding must be acquired from a combination of grants and sources within the housing association or local authority.

The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund, administered by the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero, is the main source of funding for retrofitting social homes in England. The parameters of SHDF Funding are to bring existing homes up the Environmental Performance Certificate Band C, in order to focus available funding on the worst performing buildings.

Many homes on post-war estates that are under threat of demolition will fall below Band C. However, SHDF funds only cover 50% of the works, so for retrofit schemes proposing to achieve higher than Band C there will be a considerable shortfall.

The exhibition shows a range of retrofit strategies each with a range of financial and funding implications:

At WILMCOTE HOUSE, an existing block of 107 flats was retrofitted to EnerPHit standard (the equivalent of Passivhaus for existing buildings) without residents needing to move out.

At WEST KENTISH TOWN ESTATE, alterations are proposed alongside retrofit in order to meet a similar standard as for new build housing. Lifts are installed to all existing blocks and a significant number of new building homes provided. The overall costs are therefore high in comparison.

At WEST KENTISH TOWN ESTATE, alterations are proposed alongside retrofit in order to meet a similar standard as for new build housing. Lifts are installed to all existing blocks and a significant number of new building homes provided. The overall costs are therefore high in comparison.